Abandon the last click now! – the guide for attribution newbies

With so much to say about the challenges and methods of attribution and the role of machine learning, we sometimes forget that many folks are still using last-click to measure marketing success and considering improved attribution for the very first time.

Perhaps you are new to digital marketing or analytics and you just need to know what on earth it all means!? If this is you, then here is an introductory guide to attribution – what it is, why it’s important and how you can start to get to grips with it.

What is marketing attribution anyway?

Marketing attribution is a digital version of marketing effectiveness measurement, using the deeper richer data available online. The primary question being asked is what precisely is the value of each different type of marketing activity, in terms of the sales it generates?

Answering this helps you understand what are the best opportunities for increased marketing efficiency and sales growth.

What about ‘last click wins’? What is wrong with it exactly?

If you have read anything on attribution you probably heard mention of ‘last click wins’ and maybe something to suggest you should stop relying on it. If this is all a mystery to you let’s briefly look at what it is and why measurement experts have thrown it into question.

What even the most basic digital analytics allows companies to do is anonymously track a user who visits their website multiple times, and observes whether they make a purchase or not. The company generally knows nothing about these users except their very rough location, what time they access the site and what type of browser and device they are using. All ‘last click wins’ attribution does is link any purchases made to the very last visit the user made to the site before purchasing.

So you might shop around, read up some advice, ask friends on social media, click on one or two different sellers, search again for the first one you liked, and then buy something. The final ‘search again’ action would ‘win’ under the last-click attribution rule, which means that the web and advertising analytics systems would automatically assign sales to that ad channel, for example to ‘branded search click’, and zero value to the earlier visits.

When the company evaluates their digital marketing, the effect of this last-click rule is that their evaluation is locked into this rather big assumption: that the final marketing interaction was the deciding factor in causing you to make that purchase. When you consider that some of these interactions might just be ‘exposures’ to banners or videos, you can start to understand why there might be a problem here. But the biggest problem with the last click wins assumption is that when buying online, especially for larger complex purchases like financial services or holidays, people generally go through a process, or ‘funnel’, from awareness of what is on offer through to consideration, research and then finally a purchase decision.

Marketing is based on the idea that this funnel process can be influenced which calls into question the logic of only evaluating the final action the customer makes before buying? Last-click is too late in the process: it is often a navigational action taken by a customer after they have already made up their mind to purchase.

This ‘last click wins’ attribution logic is still the primary measurement rule used in digital marketing systems. The last click is easy to measure and suits quick low-value purchases driven by performance-only marketing. However, as user behavior and retail continues to move more heavily online, the length and depth of customer interactions before the purchase have become way too complex to measure in this simplistic way.

Reliance on last-click means many companies are undervaluing digital ‘upper funnel’ marketing activity such as generic search, social, video, and email – to name but a few – and overvaluing low funnel channels like brand search, voucher code sites, and retargeting ( – some big generalizations here, in fact, all of these channels can work in different ways so you need to evaluate this yourself).

It follows that if the measurement bias due to last-click could be addressed in some way, then companies could make big improvements in marketing efficiency and sales growth, simply by re-allocating marketing budget away from the perceived high performing channels and into the real marketing drivers of sales.

How did it get to this? And why does it matter?

Marketing effectiveness measurement has been around as long as marketing itself. Imagine yourself in a pre-digital age, trying to measure your marketing. At first, it was easy – just count the number of sales you get when doing some new marketing activity. This is particularly easy to understand for direct marketing activity, like old-fashioned knocking on doors to sell something. For example, you knock on 1000 doors and make 200 sales then your marketing makes 2 sales for every 10 doors knocked on. Add in costs and revenue and this allows you to work out of it is actually worth knocking on any more doors or if it’s better to try a different approach. You can think of this as the real-world analog of last-click wins attribution.

Once a company gets larger it tends to introduce more brand marketing activity – such as posters, TV, or print. This branding activity does not usually lead to immediate sales but instead helps develop a brand reputation and position the brand as having certain features or emotional attributes. The impact of brand marketing is thus generally expected to occur over a longer period of time than more direct activity. What this means for measurement is that future sales, maybe over an extended period of time, could benefit from this brand marketing, and so this should somehow be factored in. Maybe you now sell 20% more, because some of your new customers feel they have ‘heard of you’ before. Getting to this 20% figure is quite hard since the influence of brand marketing will generally occur at the same time as other more direct marketing that carries on day by day.

Another change that takes place as companies grow is that they introduce more marketing channels that increasingly run concurrently. For example, they might introduce overlapping marketing activities such as maybe posters, plus print, plus in-store promotions. This channel overlap makes the measurement task much harder, as you don’t want to ‘attribute’ all your new sales to all of these channels at once, or else you risk over counting the sales and overvaluing your marketing effectiveness.

Eventually, as marketing budgets grow it starts to make sense to ask some clever stats people to make sense of all the marketing spend and sales data. As nineteenth-century Philadelphia retailer John Wanamaker supposedly said: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half”. Before digital came along, the state of the art in marketing measurement was ‘market mix modelling’ which is a technique still used to find statistical relationships between marketing spend on different channels and sales, intending to optimize the marketing mix i.e. the best share of the budget for each channel to get the most sales for your budget (incredibly some companies still charge 1000s to do textbook market mix modelling even to evaluate digital marketing! – more on this later…).

The difference with digital is that we now have this new much more granular data about how different visitors interact and make purchases. Enter digital attribution. The challenge it tries to address is how to use this more granular data to do the same thing as market mix modelling but on a much more granular and detailed level, moving beyond ‘last click wins’.

What is an attribution model?

An ‘attribution model’ is simply the algorithm that assigns sales value to the various marketing channels that might be involved in driving that sale. Remember an ‘algorithm’ can be a very simple rule, and so ‘last click wins’ is actually an attribution model (so in a way, everyone is doing attribution modelling whether they are aware of it or not!).

Beyond this then we have to distinguish between ‘rules-based’ and ‘data-driven’ attribution models. A rules-based model (also known as ‘positional attribution’) is a model which takes the data on a series of interactions and then applies a simple rule to share out the value. Typical models are –

- • Last-click wins – is problematic, see above

- • First-click wins – good for new customers, but how far back in time do you go?

- • Linear – credit shared equally between all touchpoints

- • U shaped – credit first and last click 40% each, 20% for middle touchpoints

- • L shaped – credit the first 60% and 40% to all the rest (%’s may vary)

- • Time decay – more credit the closer the point is in time to the last click

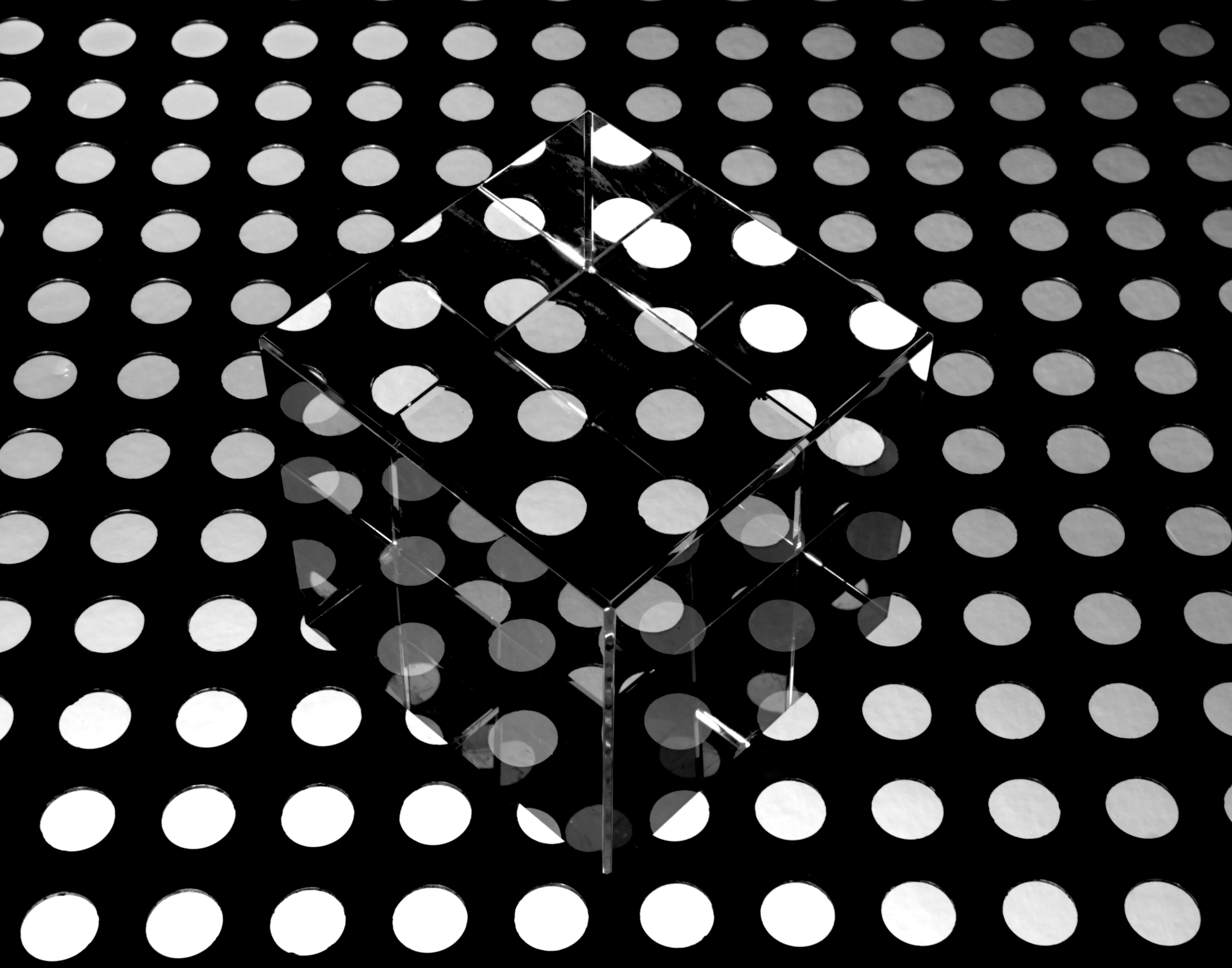

The key benefit of these rules-based models is that they are relatively simple to apply and understand, and so provide a quick and easy way to sense check last-click attribution and see how advertising is working throughout their online journey. The downside is that it can seem like entering a hall of mirrors where there is no longer a true picture of what is going on.

A ‘data-driven’ model, on the other hand, promises to solve the problem once and for all. Data-driven attribution covers a wider range of algorithms, together with the idea that the model has some basis in evidence defining that particular model as superior or more ‘accurate’ than other attribution models.

(It should be stressed that ‘data-driven’, does not necessarily exclude ‘rules-based’ models, as it might be that data analysis is used to define the particular time windows and positional and channel weights applied in a ‘rules-based’ model.)

While data-driven models seem to offer the perfect solution, they have challenges all of their own. There is a huge range of possible ways to get a data-driven model, and rival data scientists and companies all claim that their approach is the best, so there is, in fact, no one true data-driven model. The quality of the data is always worth considering, as ‘garbage in garbage out’, can skew even the most sophisticated methodology. Major questions exist about how to evaluate such models as accurate or not, and what the right criteria for ‘accuracy’ even are for this problem. Newcomers to the topic are advised to be wary of attribution vendors who sweep all these problems under the carpet and insist that their model is somehow the one true model that will solve the attribution problem once and for all.

What are some of the other key attribution issues?

There are lots of attribution topics we have not even covered here. Some major ones that most companies cannot really ignore include –

- • Attribution for users who switch between devices e.g. research on mobile, then buy on desktop

- • Online meets offline e.g. where online sales are influenced by TV ads, or where online marketing leads to sales in stores

- • Managing impression vs. click attribution, including the role of social media

- • Linking attribution to Customer Lifetime Value, and valuing repeat Vs new customers

- • Making attribution analysis fast and transparent enough to be tactical and actionable

Each of these topics deserves a long post in itself – for now, be aware that each of these is a complex topic giving rise to many alternatives theories and methods.

How do we get started on attribution?

Understanding the full scope of the challenge means you have already got started. It should be clear from this that there is no simple fix to addressing all the attribution challenges you might face. So a good place to start is to think through and prioritize which attribution issues to tackle first.

To do this, first review the current marketing budgets and how they are allocated. How good is the measured ROI of your largest channels, and could it suffer from attribution bias and error in terms of how value is attributed to each channel?

The quickest way to then challenge your existing assumption is usually not to jump in with a full-blown data-driven modelling project, but rather to look for evidence in the form of simple marketing tests and simple rules-based models which explore alternative hypotheses about how value is created.

It is important to understand that developing improved attribution is part of developing a data-driven marketing approach, which in turn is part of developing a broader data analytics capability. This is a process, not a quick fix. You will need to demonstrate the benefits that you will undoubtedly see in terms of more efficient sales growth from your marketing, and then use that evidence to justify investment in a more robust sustained approach.

There is plenty more online about attribution, but hopefully, if you read this far, you should at least now have a better idea of what it is all about.

Good luck getting to the next level and do get in touch if you think we can help.

Gabriel Hughes PhD

Can we help unlock the value of your analytics and marketing data? Metageni is a London UK-based marketing analytics and optimisation company offering support for developing in-house capabilities.

Please email us at hello@metageni.com